The contract for the purchase of the Cape 1672

In the spring of 1672, a formal land purchase agreement was reached between the Dutch settlers at the Cape of Good Hope and the indigenous Khoi tribes of the Cape.

At this time, the Khoi tribes were divided as the tribes on the West coast did not recognise the leadership of the Chainouquas who were the largest tribe. The settlement at the Cape also had a leadership vacuum as Commander Hackius had died and Commander Goske had not yet arrived at the Cape.

While Commander Hackius was ill and unable to fulfil his duties, these fell to his second in command Cornelius de Cretzer, who was an active member of the government at the Cape and was well-liked by both the government and the burghers and his superior officers. He was considered to be honest, capable, and attentive to his duties. Commander Hackius died in late November 1672.

While De Cretzer was in command, a dinner party was held where De Cretzer disagreed with two of the guests, one a captain of a ship anchored in Table Bay and the other a passenger from the same ship. This heated argument caused the captain to attack the passenger, De Cretzer was not able to warn him and De Cretzer stabbed the captain with his rapier.

Due to this unfortunate incident, he went into hiding and later escaped to Amsterdam to argue his case. The directors of the VOC found him blameless, however, he never returned to the Cape as the ship he was on was attacked by Moorish pirates.

De Cretzer had filled three positions immediately below the commander so in his absence and after the passing of Commander Hackius, there was no senior person available in the position. The governance of the Cape fell to the Politieke Raad represented by Lieutenant Conrad van Breitenbach the secretary of the Raad was Hendrik Crudop.

To address the leadership issues at the Cape, the VOC made three appointments: Isbrand Goske as Commander, Albert van Breugel as Secunde and Pieter de Neyn as fiscal. Von Breugel arrived at the Cape in March 1672 before Goske and in the meantime took charge of the settlement. Sometime later a ship returning from the East brought Commissioner Arnout van Overbeke to the Cape. As the highest-ranking official of the VOC, he inspected the settlement and concluded that a formal purchase of land from the Khoi tribes would bring some stability. Hendrik Crudop as the secretary proceeded with the arrangements for the negotiations…

The Dutch negotiation team included Arnout van Overbeker (Commissioner), Albert van Breugel (Sekunde), Conrad van Breitenbach (on behalf of the Politieke Raad), Lieutenant Johan Coon (of the Garrison), and Hendrik Crudop (Secretary).

The Khoi representation

A message was sent to the Goringhaiqua (“Kaapmans”) who owned the western part of the Dutch settlement. They were led by Osinghkamma who was known to the Dutch as Prince Schacher. Prince Schacher was the son of Gogosoa whom Van Riebeeck met in the Cape when he first arrived.

It is told that Gogosoa lived to the age of a hundred years and died in the same year that Van Riebeeck left the Cape. The Goringhaiqua were the leading tribe and they also spoke for the Gorinhaikonas (“Strandlopers”) and Cochoquas (“Saldanhars”).

A second message was sent to the Chainouqua tribe that lived in the area today known as Baardskeerdersbos, Gansbaai, and Grabouw. They owned the eastern part of the Dutch settlement at the foot of the Hottentots Holland Mountains and were the largest Khoi tribe at the time. When Van Riebeek arrived at the Cape their chief was Sousoa who had the title “Khoeque” (Paramount chief of all landowners and kings) Sousoa was regarded as “The chief of chiefs” After his death this title passed to his son Goeboe who also died and the chieftainship passed to another of Sousoa’s younger sons Dhouw who was, therefore, the hereditary heir to the land at the Hottentots Holland. His uncle Cuiper acted as regent.

Crudop invited Schacher and Cuiper with Dhouw to the Castle for the land purchase negotiation.

Background to The Agreement*

Jan van Riebeeck was sent to the Cape to create a halfway station where ships en route to the East could replenish their food and water supplies. The original idea was that Van Riebeeck would buy the needed provisions from the indigenous tribes. He set out with this planned model for the station, but he soon learned that the food supply from the Khoi tribes was not reliable and that there would not be enough to supply passing ships with the needed provisions. He convinced the management of the VOC to allow the establishment of farms. These would be independently run by Vryburgers who would be able to deliver their produce to the company. This was approved and the Vryburger settlements started.

As more and more produce was required by the company to supply the ships, the Vryburger settlements grew in proportion. More and more land was needed by the settlers to be cultivated for food production. Over time these settlements grew and penetrated further into the land that belonged to the Khoi. This, of course, led to conflict and instability in the settlement.

The Agreement for the purchase of the Cape 1672

At the land negotiations between the VOC and the Khoi tribes of the Cape, it was agreed that the Vryburgers would restrict their settlements and that the Khoi would not use these areas for grazing. The Khoi delegation undertook to sell this land to the VOC. In exchange, the Khoi could take provisions from the Castle storage for the agreed amount.

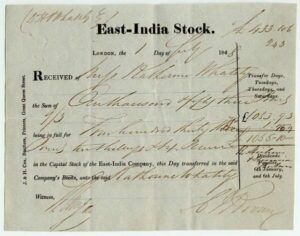

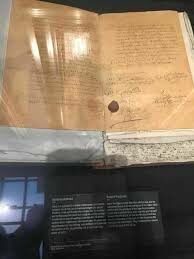

The agreement is currently preserved in the registry of deeds in Cape Town and is regarded as a legal document. There are eight clauses which read as follows:- ( see featured image)

- That the Khoi prince (referring to Schachen) agrees that he and his heirs in perpetuity will sell to the East India Company (VOC) The district of the Cape included Table Bay, Hout Bay and Saldanha Bay, with all the lands, rivers, and forest there-in and pertaining thereto, to be cultivated and possessed without remonstrance from anyone. With the understanding, however, that the prince with his people and cattle shall be free to come anywhere near the outermost farms in the district, where neither the Company nor the vryburgers required the pasture, and would not be driven away by force or without cause.

- The Khoi prince agreed that he and his people would never do harm of any kind to the Company or its subjects, and would allow them the right of transit and trade not only in the ceded district but in his other possessions.

- The Khoi prince promises to repel all other Europeans who may attempt to settle in the district.

- The Khoi prince engages that he and his descendants forever shall remain the good friends and neighbours of the Company, and be the enemies of all that seek to do the Company or its subjects harm.

- The Company (VOC) engages to pay Prince Schachen with goods and merchandise such as he may select to the value of 800.

- The Company (VOC) guarantees the Khoi the peaceful possession of the remaining territory and gives them the right of passage through the Company’s ground wherever exercise of this privilege may not cause damage or annoyance to the Company or its subjects.

- The Company (VOC) secures Prince Schachen the right of refuge in the Company’s territory in the case of his being defeated by his enemies and binds the company to protect him. It also refers to tribal disputes to the decision of the Company and provides for a present to be made yearly to the protecting power.

- The Khoi prince Schachen acknowledges that the foregoing has been translated to him he agrees to all, and that he has received the amount stipulated.

This agreement was signed on behalf of the company by Aernout van Overbeke, Albert van Breugel, Coenrad van Breytenbach, and J. Coon. For the Khoi tribes under the Goringhaiqua (“Kaapmans”), it was signed by Prince Schachen and his second-in-command ‘T Tachou. The document was signed and witnessed by the secretary, Hendrik Crudop.

A second proposal, which was identical to the one signed with Schachen was presented to the Chainouqua tribe. This was for the area next to the Hottentots-Holland Mountains with all its lands, streams, and forests. The agreement included all of False Bay. These areas were ceded to the company for 800 pounds.

The document dated 19th April 1672 and signed at the fortress of Good Hope is considered a legal transaction. By modern standards, it is considered possibly an unfair bargain where the two parties did not have equal bargaining power. The lands which were transferred in the agreement were already largely settled by the Dutch. The tribes didn’t lose any land that was not already settled, but had they refused to agree, they would have lost the protection promised to them in terms of the agreement.

About the payment of 800 pounds, it transpired that the actual value of goods transferred was nowhere near the agreed value. Furthermore, the land sold by the Khoi prince to the Dutch was land that had been taken from other tribes with force.

*When Isbrand Goske arrived later in 1672 as the new commander of the Cape, he congratulated Crudop for his administration of the agreement. He promoted Crudop to the position of Onderkoopman – which was the lowest rank of those who were allowed to negotiate deals and manage trade posts for the company (Jan van Riebeeck was a Koopman who managed the trading post in Tonkin, Indo-China, before his assignment to the Cape). Pieter de Neyn also arrived that year to take care of legal affairs – this was the first fiscal at the Cape.

More Vryburgers were settled on the land which was bought from the Khoi and when the French Huguenots arrived in 1688, farms were allocated to them based on the Crudop agreement. By 1714, there were more than 400 of these farms. The Crudop agreement was the first land transaction between European settlers and the indigenous tribes of the Cape.

.