The French Huguenots and Their Lasting Impact on the Western Cape

The Huguenots were French Protestants who followed the Reformed tradition inspired by the teachings of John Calvin. From the mid-1500s, they formed a significant religious minority in France. Their story is shaped by faith, politics, persecution, and exile. While their origins lie in Europe, their legacy is deeply rooted in the Western Cape, where a small group of refugees left an influence far greater than their numbers.

Origins of the Huguenots in France

The Protestant Reformation reached France in the early 16th century. Calvinism attracted many followers, particularly among parts of the nobility and the urban middle class. These French Protestants became known as Huguenots, a term that was originally used in mockery and whose exact origin remains uncertain.

By the mid-1500s, Huguenots made up a significant portion of the French population, possibly as much as ten per cent. They were concentrated mainly in western and southern France, including areas such as Normandy, Poitou, Gascony, Languedoc, and the Cévennes. In these regions, some towns and villages became strongholds of the Reformed faith.

Religious Conflict and Persecution

As the Huguenot population grew, so did tension with the Catholic majority and the French crown. These tensions erupted into the French Wars of Religion, a series of violent conflicts between 1562 and 1598. These wars were marked by massacres, shifting alliances, and widespread instability.

One of the most infamous events was the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in 1572, when thousands of Huguenots were killed in Paris and other cities. Although exact numbers are debated, the massacre left a deep scar on the Protestant community and accelerated emigration.

In 1598, the Edict of Nantes brought a measure of peace. Issued by King Henry IV, it granted the Huguenots limited religious freedom and legal protection. For several decades, this allowed Protestant communities to survive within France, although tensions never fully disappeared.

Revocation and Exodus

The situation changed dramatically under King Louis XIV. Determined to enforce religious unity, he gradually restricted Protestant rights. In 1685, he revoked the Edict of Nantes through the Edict of Fontainebleau, making Protestantism illegal in France.

Churches were destroyed, schools closed, and many Huguenots were forced to convert or flee. Soldiers were often billeted in Protestant homes to intimidate families into conversion. As a result, hundreds of thousands of Huguenots left France, creating one of the largest refugee movements in early modern Europe.

Most fled to Protestant regions such as the Netherlands, England, Switzerland, and parts of Germany. A smaller number travelled much further, including to the Dutch Cape Colony at the southern tip of Africa.

Arrival at the Cape of Good Hope

Huguenots began arriving at the Cape in small numbers before 1688, but the main group settled between 1688 and 1689. In total, just over 200 French Huguenots settled permanently at the Cape. While this was a small community, it represented a substantial portion of the free European population at the time.

The Dutch East India Company supported their settlement. The Huguenots were fellow Protestants and were valued for their farming skills, craftsmanship, and strong work ethic. The Governor of the Cape, Simon van der Stel, allocated land to them mainly in the Drakenstein area, present-day Paarl, and in the valley that would become known as Franschhoek.

Settlement in Franschhoek and Surrounding Areas

The Huguenots were initially settled along the Berg River Valley, but many found the soil there unsuitable. They identified better land in a secluded valley known as Olifantshoek. In 1694, several farms were allocated to French settlers in this valley, which was then renamed Franschhoek, meaning “French corner”.

Farms were also established along the Dwars River. Many settlers named their farms after places they had left behind in France, such as La Motte, Provence, La Brie, and Chamonix. These names still appear on wine farms and maps across the Western Cape.

Van der Stel deliberately dispersed the Huguenots among Dutch settlers rather than allowing a separate French community to form. This policy encouraged integration and ensured that the French language and customs did not persist as a distinct identity for long.

Religion and Early Community Life

To support the French-speaking settlers, the Dutch East India Company sent a minister, Pierre Simond, to the Cape in 1688. He conducted services in French in Drakenstein and Stellenbosch and played an important role in organising the early Huguenot community.

However, official policy soon required all schooling, church administration, and legal matters to be conducted in Dutch. By the early 1700s, French-language church services had ended. Within two generations, French had largely disappeared as a spoken home language at the Cape.

Agricultural and Economic Influence

The Huguenots had a lasting impact on agriculture in the Western Cape, particularly in viticulture. While wine production existed at the Cape before their arrival, it expanded significantly after the late 17th century.

Many Huguenots came from wine-producing regions of France and brought practical knowledge of vineyard management, pruning, and winemaking. Historical records show that Huguenot farmers were often more productive than their counterparts and played a key role in improving the quality of Cape wine.

They also contributed to wheat farming, livestock rearing, and various trades. Over time, their agricultural success helped stabilise the colony’s economy and supported the growth of rural settlements in the interior of the Western Cape.

Assimilation into Cape Society

Despite their strong identity as refugees, the Huguenots assimilated rapidly. Their shared Calvinist beliefs made integration with Dutch settlers relatively easy. Intermarriage became common, and by the early 18th century, the Huguenots no longer formed a separate cultural group.

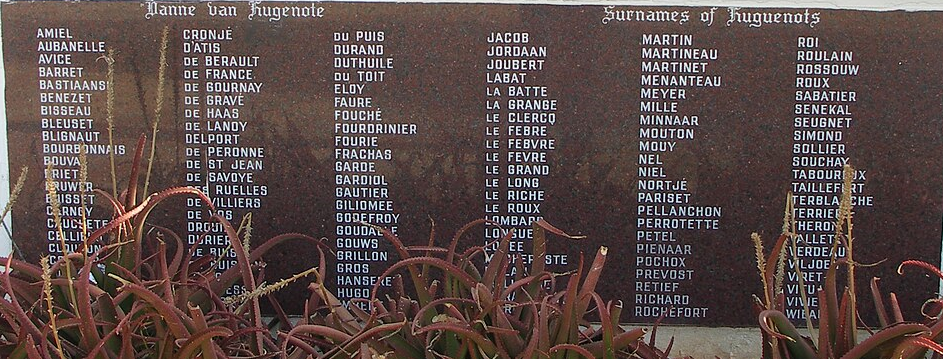

French surnames, however, remained. Many were preserved in their original form, such as De Villiers, Du Toit, Malan, Du Plessis, and Le Roux. Others were adapted over time, including Viljoen, Cronjé, and Pienaar. These names are still common across the Western Cape and South Africa today.

Demographic and Cultural Legacy

Although the original Huguenot group was small, their descendants became numerous. Research suggests that Huguenot ancestry makes up a significant portion of the modern Afrikaner gene pool. Many individuals with Huguenot surnames went on to play prominent roles in farming, religion, politics, education, and public life.

The Huguenot influence is also preserved in place names, farm names, and institutions. Franschhoek remains the most visible symbol of this heritage, with its memorial, museum, and continued association with wine and French-inspired place names.

The Huguenots in the Western Cape Today

Today, the Huguenots are remembered not as a separate community, but as part of the broader foundation of Western Cape society. Their story is one of forced migration, adaptation, and long-term contribution rather than cultural dominance.

What remains is a quiet legacy: vineyards laid out along mountain slopes, family names carried through generations, and towns shaped by early farming networks. The Huguenots did not reshape the Cape overnight, but over time, their skills, resilience, and values became woven into the fabric of the region.

Why the Huguenot Story Matters

The history of the Huguenots helps explain why certain areas of the Western Cape developed as they did. It connects European religious politics to local landscapes, farms, and towns. It also shows how small groups of settlers, under the right conditions, can have a lasting influence without remaining culturally distinct.

In the Western Cape, the Huguenots are best understood not as outsiders, but as early contributors whose legacy endures in geography, agriculture, and family histories, rather than in language or separate institutions.

Their journey from persecution in France to settlement at the Cape remains one of the most significant migration stories associated with the region’s early history.

Main image: Huguenot memorial in Franschhoek