The Dutch East India Company (VOC) and Its Role in South Africa

The Dutch East India Company, known as the VOC (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie), was founded in 1602 and became one of the most powerful trading companies in world history. It was the first company to issue publicly traded shares and operated on a global scale long before modern corporations existed. Although its main focus was trade in Asia, the VOC played a decisive role in shaping South Africa’s early colonial history, particularly through the establishment of the Cape settlement.

Why the VOC Was Formed

At the end of the 16th century, European demand for spices such as cloves, nutmeg, and mace was extremely high. These goods were valuable not only for food but also for medicine and preservation. At the time, the Portuguese controlled most of the spice trade routes to Asia. Several small Dutch trading companies tried to break this monopoly, but competition between them weakened their efforts.

To solve this problem, the Dutch government forced six rival companies to merge into a single entity. This merger was strongly supported by Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, a Dutch statesman who believed that a united trading company could strengthen the Dutch economy and help fund the fight for independence from Spain during the Eighty Years’ War.

On 20 March 1602, the States General of the Dutch Republic granted the VOC a 21-year charter, giving it exclusive rights to trade in Asia. The company was also allowed to wage war, build forts, appoint governors, mint coins, and sign treaties. In effect, the VOC operated like a state.

How the VOC Was Organised

The VOC was divided into six regional chambers (kamers) based in major Dutch port cities: Amsterdam, Zeeland (Middelburg), Rotterdam, Delft, Hoorn, and Enkhuizen. Each chamber managed its own ships, warehouses, and staff.

Overall control rested with the Heeren Zeventien (Gentlemen of Seventeen), the central board of directors. Amsterdam dominated the company financially, contributing more than half of the initial capital of 6.4 million guilders, but smaller chambers were given rotating seats to balance influence.

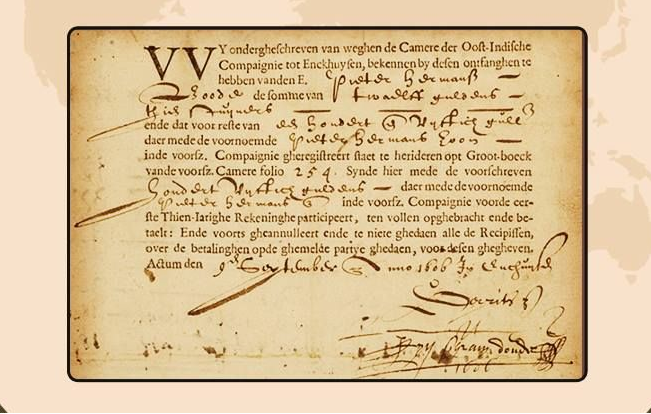

One of the VOC’s most innovative features was its financial model. Members of the public could buy shares, making it the world’s first publicly traded company. Initially, the charter required the company to be dissolved after ten years, but its commercial success led the government to allow it to continue indefinitely.

The Cape of Good Hope and South Africa

South Africa entered VOC history in 1652, when Jan van Riebeeck established a refreshment station at the Cape of Good Hope. The Cape was never intended to be a major colony at first. Its purpose was practical: to supply fresh water, meat, vegetables, and medical care to VOC ships travelling between Europe and Asia.

The Cape’s location made it essential to the VOC’s trade network. Voyages to Asia could take up to three years, and ships needed a reliable stopover. Over time, the refreshment station grew into a permanent settlement, supported by free burghers (settlers), enslaved labour, and VOC officials.

The Cape soon developed its own infrastructure, including reservoirs, canals, farms, and fortifications, such as the Castle of Good Hope. Slavery became central to the colony’s economy, with enslaved people brought from East Africa, Madagascar, India, and Southeast Asia. These early systems shaped South Africa’s social and economic foundations for centuries to come.

Building a Global Spice Empire

While the Cape supported VOC shipping, the company’s real wealth came from Asia. In 1605, the VOC captured the Portuguese fort at Ambon in the Spice Islands, securing control over the clove trade. This marked the beginning of a powerful monopoly enforced through treaties, military force, and strict controls.

In 1619, the VOC established Batavia (modern Jakarta) as its main Asian headquarters. Under Governor-General Jan Pieterszoon Coen, Batavia became the administrative and commercial heart of the VOC’s empire. Coen believed strongly in using force to secure trade dominance.

Jan Pieterszoon Coen

The most brutal example of this policy occurred in 1621 on the Banda Islands, the only source of nutmeg at the time. VOC forces killed or expelled most of the local population and replaced them with enslaved labour. This gave the VOC complete control of the nutmeg trade and enormous profits for more than a century.

VOC Trade Networks Across Asia

The VOC built an extensive trading network across Asia:

-

Ceylon (Sri Lanka): Controlled cinnamon production and exports.

-

India: Traded textiles, silk, indigo, and cotton from ports such as Surat and Pulicat.

-

Formosa (Taiwan): Operated Fort Zeelandia and traded silk, silver, and gold.

-

Japan: Restricted to the island of Dejima but highly profitable, especially through silk trade.

-

Southeast Asia: Controlled spice production and shipping routes.

Goods moved through a complex intra-Asian trade system, with silver, textiles, and spices circulating before final shipment to Europe.

Exploration and Mapping

VOC trading ambitions led to exploration far beyond known routes. From Batavia, the company sponsored voyages to chart unknown coastlines and assess trade potential.

Explorers such as Abel Tasman mapped Tasmania, New Zealand, and parts of Australia in the 1640s. Willem de Vlamingh later charted Western Australia and recorded the black swan. Although these expeditions produced little commercial value, they played a major role in early global mapping.

Decline of the VOC

By the late 18th century, the VOC was in serious trouble. Several factors contributed to its collapse:

-

High military and administrative costs

-

Corruption among officials

-

Competition from the British East India Company

-

Declining demand for spices

-

Smuggling and loss of monopolies

-

Costly wars and political entanglements

By 1799, the Dutch East India Company was bankrupt. The Dutch government formally dissolved the VOC, taking over its debts and territories.

The VOC’s Legacy in South Africa

The VOC left a lasting imprint on South Africa. It established Cape Town, introduced European-style governance, reshaped land ownership, and entrenched slavery and racial hierarchy. Dutch language, law, and architecture influenced later colonial systems and eventually Afrikaans culture.

Globally, the VOC set the model for modern multinational corporations. It showed how commerce, state power, and military force could combine to shape world history.

Though founded as a trading company, the VOC became a colonial power whose influence is still visible today — from Cape Town’s streets and archives to global trade systems that continue to echo its structure.

- Colourdots is an independent regional information resource for the Western Cape.

Learn more about the project HERE